Tolkien: When, Who and Why?

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien CBE was a multifarious man with an elusive identity: a scholar; an academic; a soldier; a father, but the immediate connotation of his name that prevails now, almost fifty years after his death in 1973, is of Tolkien being the ‘father of modern fantasy’[1].

J.R.R. Tolkien by Pamela Chandler.

Tolkien was born on the 3rd of January 1892 in Bloemfontein, Orange Free State that became a part of South Africa in 1910. Tolkien moved back to England in 1895 which was shortly followed by his father’s death only two years later. The Tolkien family moved to Edgbaston in Birmingham where Tolkien and his younger brother Hilary both attended St Philip’s Grammar School. However, in 1904, Tolkien’s mother, Mabel died from diabetes leaving Tolkien and his little brother to become wards of Father Morgan, one of the priests of Birmingham Oratory thus catalysing a deep connection to the Christian faith for Tolkien. In 1907, Tolkien created his first language ‘Naffarin’ using his knowledge of Spanish and Latin learnt at King Edward’s; this inclination to languages would become increasingly dominant in Tolkien’s life and develop to be a major aspect of his personal identity. Tolkien was gifted a scholarship to Oxford’s Exeter College in 1910 where his first piece of work was published, the poem The Battle of the Easter Field’ a parody of Thomas Babbington Macaulay’s The Lays of Ancient Rome’[2]. In the Summer Term of 1911 at Oxford, Tolkien and a group of close friends created the ‘Tea Club, Barrovian Society’, the ‘big four’ of the T.C.B.S at the time being: Tolkien; Geoffrey Bache Smith; Christopher Wiseman and Robert Gilson[3]. The T.C.B.S in its basic format was a literary discussion and criticism group where the members shared their works among themselves. When World War One started in 1914, Tolkien went back to Oxford and got a first-class degree in English Language in June 1915. Following this in 1916 he enlisted and was immediately on active duty, but after four months in and out of the trenches, Tolkien caught “trench fever” and was sent back to England, spending a month in hospital in Birmingham but recovering before the Christmas of that year.

During the war, all members of the T.C.B.S par Christopher Wiseman[4] were killed in action, a series of events that had a profound impact on Tolkien. We see the influence of Tolkien’s experiences regarding the war and the memory of his friends shining through the stories he began to write around this time- perhaps as a coping mechanism for his grief – these stories later developing to some of Tolkien’s other major works Silmarillion and The Book of Lost Tales. Tolkien’s own illness recurred frequently between 1917-1918 when he also had periods returning to the war in France as a Battalion Signalling Officer. In 1918 Tolkien returned to Oxford employed by the New English Dictionary and in the two years following this he began working at Leeds University.After a continuation of his writing, Tolkien became the Professor of English Language at Leeds in 1924.

Tolkien continued expanding on his academic career and in 1926 C.S Lewis and Tolkien first met and became close friends, sharing a mutual love of religion and mythological fantasy writing. At some point in the summer of 1930 Tolkien wrote the first sentence of The Hobbit, the prequel to The Lord of the Rings: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit’[5]. In late 1932 Tolkien lent the typescript for The Hobbit to his new friend C.S Lewis and the book was later published on the 21 of September in 1937. In 1945 Tolkien became Oxford’s Merton Professor of English Language and Literature. Throughout the 1940s Tolkien wrote the various chapters and sections of The Lord of the Rings trilogy: The Fellowship of the Ring; The Two Towers and The Return of the King, the sequel to The Hobbit and in the Autumn of 1949, he began discussions with Collins about the publication. The early parts of 1954 were dedicated to the editing of The Lord of the Rings and getting the appendices ready for its publication that year. In the following years after The Lord of the Rings’ publication Tolkien’s trilogy was, and remains, extremely well received internationally and he is highly praised for his other works, including a translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; The Letters of Father Christmas; Pearl and Sir Orfero and Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics. To celebrate his brilliant body of work Tolkien was awarded a CBE in the New Year’s Honours List of 1972. He died a year later from a stomach ulcer.

The Journey of Tolkien’s Middle-Earth to the Big Screen

Peter Jackson- film director, screenwriter and producer- is a lifelong admirer of J.R.R. Tolkien’s works and in 1990 with Philippa Boyens and his wife Fran Walsh began the longstanding ambition and incredibly daunting feat of bringing the universe of The Lord of the Rings to life in a trio of epic instalments. Jackson’s career first began with the making of gory witty horror comedies in his homeland New Zealand and he went on to become one of the most successful and innovative filmmakers of his generation, noted as being one of directors using techniques of “Golden age Hollywood” aided by his collaboration with the SFX company Weta Digital. Over 438 days in 2000 Jackson and his crew begun the task of filming the world of The Lord of the Rings transforming Tolkien’s novels into films[6]. The films were unequivocal cinematic achievements, breaking box office records and earning numerous Academy Awards, including Best Picture for The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003). Since their release the films have gained a new following, introducing a new generation and wider demographic of people into the already cult-followed world of Middle-Earth so carefully constructed by Tolkien. Elijah Wood as Frodo Baggins; Sean Asten as Samwise Gamgee; Vigo Mortensen as Aragorn; Sean Bean as Boromir and Ian McKellen as Gandalf the Grey have become much loved and iconic ‘characters’ and with the magnitude of the films’ success may be seen as one of the only true positive representations of masculinity to come of 2000s Hollywood.

Many factors of Tolkien’s life may have impacted his perception of masculinity, and through the process converting this masterpiece of literature to screen Jackson dedicated himself to staying true to Tolkien’s nuances. Whether it was Tolkien’s exposure to the archaic hegemonic models prevalent in the academic sphere or his experience in living in 1900s Britain; cumulatively these influences would play a crucial part in producing Tolkien’s own interpretation of hegemonic gender that shines in The Lord of the Rings.

Hegemonic Masculinity through the development of society

During the Classical Period, the pinnacle hegemonic masculine traits were the five cardinal virtues: wisdom; moderation/temperance; bravery; justice and piety. Collectively these qualities would create the attributes essential to excelling in war and battle, the most likely occupation for Greek men. Scott Rubarth suggests that ‘Greek conceptions of masculinity are intimately tied to the virtue of courage as the very word that we translate as courage, andreia, comes from the Greek word for a male adult, anêr/andros and can be translated as manliness’[7]. Iconic feminist historian, Mary Beard proposed that ‘toxic masculinity’ may have roots dating back into Greek culture[8]. It is undeniable to see how Greek myths are overpopulated with monstrous or otherworldly glorified rapists, whereas for women we see the infamous misinterpretation of the myth of Medusa- perhaps being an early example of victim-blaming in a highly patriarchal society. However, this convention of toxic masculine heroes in the genre is challenged in Hippolytus[9], as the titular male hero challenges sexual norms through celibacy- some may now identify this as one of the first accounts asexuality. The hero preferred to spend his time outdoors proving hegemonic masculinity was not simply defined by the destructive acts of abuse of the warriors in the myths popular at the time.

Phaedra and Hippolytus, Pierre-Narcisse Guerin (1774-1833)

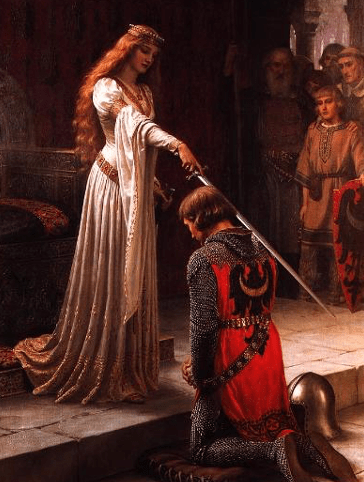

The ‘Seven Knightly Virtues’[10] of the medieval period have striking similarities to the Greeks, suggesting that during the early cultures of mankind the hegemonic model of masculinity had an element of stagnancy. In society we again see hegemonic masculinity defined by a dominating group of characteristics – the five cardinal virtues of the Greeks became the five virtues of knights: friendship; generosity; chastity; courtesy and piety. The Code of Chivalry was a moral system which went beyond rules of combat and introduced to society the concept of Chivalrous conduct for men. The qualities of the Code of Chivalry[11] were emphasised by the oaths and vows that were sworn in the Knighthood ceremonies of the Middle Ages and mediaeval era. In the early 11th Century during the rule of William the Conqueror, the Song of Roland [12] was written, outlining the oaths included in the Code of Chivalry of the 8th Century Knights: ‘to respect the honour of women, to live by honour and for glory, to fight for the welfare of all’. In the 12th century a Frenchman named Andreas Capellanus wrote the Rules of Courtly Love[13] emphasising on the importance of the concept of great gallantry towards women, as illustrated in the story of Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere[14].

The Accolade, by Edmund Blair Leighton (1901)

Being a key scholar in the field of English Language specialising in Old and Middle English who would then go to become a professor of Anglo-Saxon (Old English) at the University of Oxford[15] it is unequivocable the virtues of this era would have impacted Tolkien’s perspective on masculinity greatly.

During WW1, as masculinity and militarism became intimately linked, the hegemonic idea of masculinity evolved within Western society and moved away from the previous archaic tropes. When the war swept across the world it unconsciously became interlinked with “manhood”, defined by courage, strength, and the spirit of sacrifice, especially for young educated men across Europe. Sonja Leveson[16] suggests that ‘the First World War represents the apex of the idea of the male warrior hero’. Tolkien himself had experience fighting in this war, enlisting as a 2nd lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers and going to active duty on the Western Front for the Somme offensive[17]. The war became a symbol of masculinity in British society, the Order of the White Feather[18] founded as a propaganda campaign weaponizing shame in a political effort to get men to sign up and join the fight, thus associating the white feather with cowardice, dereliction of duty and femininity[19]. Universally we see patriarchal societies defining hegemonic feminine traits as undesirable, so when a man embodies one of these traits society creates and conveys a powerful element of shame. Being perceived as unmanly would be considered the peak of “failure” for a man in a patriarchal society, being, for example, at the root of the assertion ‘boys don’t cry’ as emotional availability is defined as a hegemonic feminine trait. This can be seen being emulated in Britain through the symbol of the white feather; it has been speculated to have derived from the history of cockfighting a white tail feather of a rooster meant that the bird was considered inferior for breeding and lacked aggression[20]. Here we see masculinity as a fine binary of regimented active behaviours defined by enlisting in the army, the sole manner by which one may be able to meet the hegemonic model of masculinity at that time – a time of war.

In current Western society there is has been identified a rise of a culture fostering and embracing toxic masculinity showing blatant misogyny. There are high levels of young men falling into alt right pipelines[21]. This cohort of men dub themselves ‘incels’[22] short for involuntary celibates, existing in online enclaves that have become echo-chambers of extreme misogyny, developing a strong and increasing presence in society, performing acts of violence against women. In 2014, Elliot Rodger killed six and wounded fourteen people in a shooting spree in Santa Barbara, California[23] justifying his actions in a manifesto, My own Twisted World[24], published on the internet as retaliation against women as a group for refusing to provide him with the sex he claims he is ‘owed’ and ‘entitled’[25] to. In 2018[26], Alek Missani, inspired by Rodgers who has become a “martyr” for this group of radical misogynists, killed ten people by driving a van into pedestrians with the intent of murdering women. Here we can see an almost satirical extreme degradation of and complete contrast to the ideals of the Rules of Courtly Love. Perchance the models of masculinity existing in media have strayed too far from the hegemonic model and negatively re-defined it: in the film Taken[27], Liam Neesom’s character reacts to his daughter’s kidnapping with irrational and illogical levels of violence akin to Keanu Reevescharacter in John Wick[28]. The paradox here is not the tremendous graphic and violent content of the films, it is that Reeves’ and Neesom’s characters are the “hero” or per say “good guys” inherently glorifying the qualities and behaviours of these male characters by suggesting they are exemplary and admirable.

Recently, on Tik Tok and YouTube Andrew Tate[29] attracted massive attraction for his spewing of “gender politics”, some of his videos reaching 11.6 billion views[30] in which he thinly veils misogynistic rhetoric by claiming he identifies with “traditional” views of gender- particularly of masculinity. He claimed that ‘the masculine perspective is you must understand that life is war. It’s a war for the female you want. It’s a war for the car you want. It’s a war for the money you want. It’s a war for the status. Masculine life is war’[31]. The perspective of the ‘masculine life’ has arguably become dominated by the ideals surrounding women as sexual objects, monetized for masculine validation- the peak of success dictated by the patriarchy.

Another preacher of masculinity and debater of gender politics that blew up on the internet is Jordan Peterson. Peterson claims that most of his ‘ideas surrounding masculinity stem from a gnawing anxiety around gender’ and that ‘the masculine spirit is under assault’[32]. He perceives ‘order as masculine and chaos as feminine and an overdose of femininity is our new poison’ in society. Peterson dubbed his new book with the subtitle: An Antidote to Chaos casting his misogyny in a subtle light. Regarding the previously mentioned Alek Missani, Peterson stated Missani ‘was angry at God because women were rejecting him’ and that ‘the cure for that is enforced monogamy’. The majority of Peterson’s preaching’s focus on the ‘importance of enforced monogamy as a rational solution and proposes society needs to work to make sure those men are married’ to solve this gender crisis[33]. Peterson has some strand of reason running through his overall ideology: ‘choose your destination and articulate your being’; ‘quit drooping and hunching around, speak your mind, put your desires forward’ and ‘our choices determine the destiny of the world, by making a choice, you alter the structure of reality’[34]. However, Peterson’s discord is problematic on many levels as it is mainly constructed through blaming of women as the catalyst for these extreme acts of misogynistic hate crimes committed against themselves- parallel to the Greek’s attitude towards Medusa treating her as villain rather than a victim.

Anthropologist Elizabeth Nicole Genter recently identified the ‘themes of masculinity’ prevalent in the digitally converted world: ‘misogyny; sex; coolness; toughness; material status; and social status’[35]. If looked at holistically, this proposes that the attitudes displayed regarding masculinity and its production of misogyny have in some ways radically changed, showing a sense of progression in society. However, I concur with Genter’s argument that the fundamental rhetoric of the patriarchal ideology that dictates hegemonic gender has stayed stagnate and prevailed into the 21st century. Consequently, this misogynistic rhetoric bleeds in infecting and becoming cancerous to our modern portrays of masculinity and its code of conduct losing touch with the archaic stages of masculinity. Thus, giving a profound and exceptional importance to revisit texts such as The Lord of the Rings that have survived and thrived despite this of epidemic of toxic masculinity.

Masculine Hegemonic Traits in Middle-Earth

Throughout the three books and films: The Fellowship of the Ring; The Two Towers and The Return of the King Middle-Earth Tolkien presents a cultural and generational shift from the end of the Third Age into the beginning of the Fourth Age. This evolution of society extends to the hegemonic model of gender individual to Middle-Earth resulting in the gender traits we see in the characters diversifying progressively through the trilogy. The Third Age of Middle-Earth is represented by Denethor the steward of Gondor, the greatest and most prominent kingdoms of men[36]; Boromir, Denethor’s first son and Théoden the king of the horse-lords of Rohan- Gondor’s greatest ally[37]. Beatriz Domínguez Ruiz suggested that the traits exhibited by Théoden, Boromir and Denethor ‘can be defined as hypermasculinity’[38] as for the most part they heavily conform solely to hegemonic masculinity. The new Fourth Age is, in contrast, symbolized by Frodo Baggins, a young hobbit tasked with bearing ‘the one ring to rule them all’; his loyal friend Samwise Gamgee; Faramir, Denethor’s second son and Aragorn, Isildur’s heir the true king of Gondor. The defining characteristic that differentiates this cohort of characters is that their actions and qualities encompass hegemonic masculine and feminine traits. However, due to their gender the male hegemonic traits dictate all the characters’ identities influencing the behaviour they exhibited. Gender theorist Judith Butler states that gender ‘is a performative accomplishment compelled by social sanction and taboo’ and it is ‘instituted through a repetition of acts’[39] so these characters’ actions are what identifies them as men. Tolkien illustrates the consequences of these masculine ‘repeated acts’ or characteristics and questions these ‘social sanctions’.

Confidence

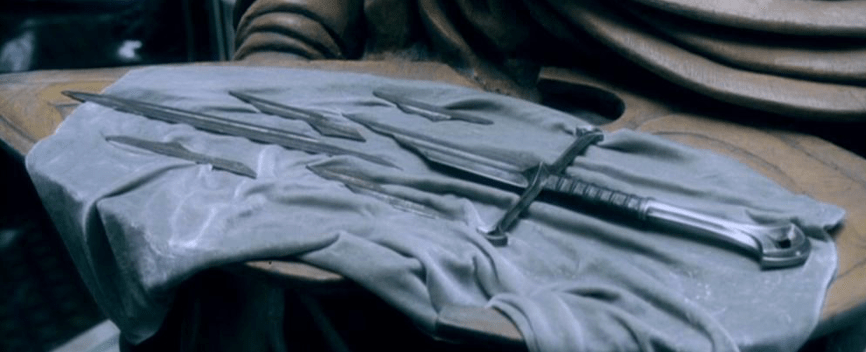

Aragorn undergoes an extreme journey of inner confidence to become the true king he is. His name, Aragorn, in Sindarin – the language of the elves – means ‘noble valour’, thus, allowing Tolkien to predispose Aragorn to readers with connotations of greatness that may not at first be apparent in his actions. The character of Aragorn when first introduced in The Fellowship of Ring does not conform to many aspects of hegemonic masculinity, aligning more with the feminine attributes. However, as his story develops, the masculine elements of himself come into focus—the main one of these is his confidence. His masculinity is represented through the sword Andúril, a common literary and cultural symbol for masculinity due to its highly phallic resemblance. The sword was used in the War of the Last Alliance against Sauron and became the shards of Narsil, kept sacred in Rivendell.

The Lord of the Ring: The Fellowship of the Ring, New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2001)

One of the most iconic quotations and thematic elements presented by Tolkien is that ‘the hearts of Men are easily corrupted’. Andúril is a physical manifestation of this concept, symbolising the mistakes made by the race of men who once caved to the power of the ring. The fragments of the sword mirror Aragorn’s relationship with the hegemonic masculine model and identity. Aragorn, much like Tolkien himself, gains a multifarious persona having different accolades to each race of Middle-Earth. To the race of men, he is Strider, the name of his ranger persona echoing more of Greek myth’s masculine hero’s, alike the word ‘manliness’ he himself is intertwined with war. He is a slight Robin Hood type character akin to Hippolytus, influenced by the gentle feminine attributes of the Elves who raised and socialised him as Estell. Ultimately, Aragorn loses the most crucial aspect of himself, that has been overshadowed in this fragmented image- he is Isildur’s heir. He must forge these identities together, like the remaking of the sword, to become one powerful whole and thus be ready to claim the throne of Gondor. It is this ‘forging’ of parts that enables his masculinity and confidence to come fully into fruition. The gifting of the re-forged Andúril to him is a symbolic moment that validates all the stages of developing confidence which Aragorn exhibits progressively through the trilogy, Tolkien creating this motif to procure an epiphanic moment where the sword is critical to complete his transition to king and to lead the battle against Sauron.

However, the moment Aragorn fully embraces the role himself and exhibits hegemonic male confidence is not in accepting the sword but when claiming a debt from the army of dead. When the army of dead deny Aragorn their service and threaten him, instead of responding with excessive violence seen in epic Greek literature and modern media, he just forcefully exclaims, ‘I do not fear death’[40], communicating his bravery and inner strength. His action of demanding the service of the dead is not of excess and greed, rather it is of absolute necessity. Unlike Denethor’s excess of confidence facilitated by his wardship of the crown, Aragorn has no sense of gluttony when it comes to power that will help him serve his own needs. Tolkien uses this moment, a scene Jackson heavily emphasizes and amplifies, to show Aragorn’s selfless commitment to the role of king. His coronation scene at the end of The Return of the King, once Sauron is defeated and the ring destroyed, is a purely a symbolic traditional societal ceremony as he has already proved himself to be the rightful king through his actions.

Tolkien offers a humbler and more relatable version of Aragorn’s transformation in the character of Samwise Gamgee, creating an underlying message on the surprisingly heroic nature of the ‘amazing’ hobbits- the race that most in tune with true positive masculine heroism. Tolkien makes a powerful comment on the situational courage found in the least likely of people. Tolkien said, ‘Hobbits are just rustic English people, made small in size’ ‘reflect[ing] the generally small reach of their imaginations — not the small reach of their courage’[41]. Hobbits embody much of Victorian-era English hegemonic traits creating an element of relatability to most European audiences. It is seen that Tolkien ‘brings the heroic world close to the modern reader through the eyes of the hobbits’[42]. Unlike Aragorn, Tolkien does not give Sam much credit in his nomenclature, Samwise is the modernized version of ‘Banazîr’ from Tolkien’s language of Westron and translates to ‘half-wit”’ or ‘simple’[43]. However, throughout the trilogy Sam subverts his namesake becoming mighty and heroic- a positive representation of male confidence. Tolkien explained that the character of Sam was inspired by the men he knew in WWI who fulfilled the role of ‘batman’, men who brought support and aid to other soldiers[44]; Tolkien saw them as ‘far superior’ to himself immediately bringing the influence of hegemonic masculinity of the 1900s to come into focus. Like Aragorn’s love for Arwen, Sam’s simple rustic love for Rosie mirrors the Capellanus’s Rules of Courtly Love: he is never overbearing or demanding in his disposition to her, instead quietly confident in himself when he returns to the Shire, affirming his positive masculinity born of their adventure and experience.

Ultimately, Tolkien subtlety presents Sam as the true main hero as his heroism has a great level of consistency. Sam’s transformation lacks the element of grandeur of Aragorn’s – he is not a king – he simply allows the hero below the surface to come into fruition through the selfless support of his friend and their quest. His bravery, against all odds, prevails and remains optimistic persevering through all the obstacles the fellowship comes across. Sam’s actions have critical impact to the success of the entire journey underpinning Frodo’s ability to destroy the ring thus saving Middle-Earth. Sam carries Frodo both emotionally and physically whatever the odds, presenting true male hegemonic confidence.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2003)

Tolkien celebrates the unobtrusive confidence with which Sam is imbued, creating a stark contrast to the brash hubris of the Greeks and the modern caricature representations of masculinity. Akin to the sacrifices of many ordinary men made in World War One, Sam recognises the danger and still dedicates himself to the mission and to Frodo exhibiting loyalty and courage. It is also significant that whilst the power of the ring tempts Sam, as it naturally tempts everyone who encounters it, Sam does not succumb to its power, this reflecting his growth in confidence, but confidence tempered with humility and selflessness.

In contrast with these characters, Tolkien illustrates the consequences of Boromir’s excess of confidence and pride. The first son of the steward of Gondor, Boromir is given an aura of false righteousness which is initially seen at the Council of the Ring in Rivendell- our introduction to the character. Tolkien uses Boromir as a comparative to Aragorn, a tool to illustrate Aragorn’s high morality against the common man. Aragorn and Boromir are the characters who most closely conform to the Medieval hegemonic model of chivalric knights[45]. They become a clear display of societal contrasting equals. Both belong to the race of Men and are experienced warriors with skill in battle, but Aragorn is also presented as the soulful, poetic knight, simultaneously valiant but melancholy. In comparison, Boromir physically looks the part, laden with the props and armour of a round table champion, and is more brazen, propelled by a knightly sense of nationalism and desire to protect his homeland and family honour. Boromir’s desire for power is primarily driven to please his father by exhibiting the qualities ascribed to him, this pressure creating a figurative dent in his armour and with it a moment for the ring to tempt his heart.

Boromir’s deluded confidence peeks when he attempts to take the ring from Frodo. Boromir knows of the ring’s ability to give him the ‘power of command’ making ‘men flock to his banner’[46] and this image of nationalism pollutes and corrupts his mind, tempting him to behave in a manner he knows to be wrong as one of the fellowship. In his moment of madness, he calls up the patriarchal concept of succession and power superstructures saying ‘why not Boromir?’, Tolkien uses the third person speech to signal his developing psychosis caused by the ring. The ring festers and builds on Boromir’s image of his masculine self and inflates it in his mind leading to his destruction morally and physically. However, Tolkien allows for Boromir to gain redemption from his destructive ‘hypermasculinity’[47] with a moment of emotional availability at his death as he confesses how this has become his weakness and threatened to splinter them all.

Assertiveness in Leadership and the paradox of Kingliness

The paradox of kingliness is presented by Tolkien through Théoden and Denethor. Although both representing the Third Age of Middle-Earth these two characters react to the adversity associated with their allocated role in two opposing ways. This contrast is primarily displayed through the trajectory of the characters: Théoden’s redemption and Denethor’s downfall.

Tolkien first introduces the character Théoden as a pale shadow of the man he once was devoid of the characteristic ‘hypermasculinity’ of the Rohir as symbolised through the houses of their banner.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2002)

Théoden’s mind had been corrupted by Saruman, however even when Gandalf lifts the spell his actions are still devoid of the greatness with which he was once imbued. Théoden regains his role as king but is insecure of his masculinity lacking the positive assertiveness of a great king. Instead of facing the enemy in battle, Théoden and the people of Rohan retreat into Helm’s Dee, illustrating Théoden’s struggle with his position of leadership. He fears the ‘risk [of] open war’[48] rejecting his sword, the symbol of his masculinity, showing a weak king who is trapped and afraid to face death. These are all acts of self-preservation for himself and his people, born out of fear and lacking Aragorn’s combination of selflessness and confidence, the quality that makes him such a great ruler.

After being attacked by the Uruk-Hai Orcs,Théoden finally appears again in his full stature as a king and warrior, a true lord who the men of Rohan willingly follow to their deaths. At the very last moment when death is upon him and his people, Théoden rediscovers the spirit of his ancestors and faces him doom with courage, inspired by the example set by Aragorn. The lighting of the beacons mirrors the rekindling of the hegemonic masculinity inside of Théoden. ‘Rohan… answers’ ‘Gondor calls for aid’[49] and Théoden rides out again, not because he seeks death or glory but because it is the right thing to do. He asks in an assertive manner, not dictatorial, for Aragorn to ‘ride out with [him]’[50] an offering of allyship to rebuild the relationship between the two great nations of men in Middle-Earth. Influenced by his time in WW1 Tolkien perhaps valued the will to fight and the courage to sacrifice oneself, instead of attempting to achieve glory through great deeds of violence or death seen in Greek myths. Théoden not only achieves a physical victory but a spiritual and moral victory too. Théoden achieves this when he shows valour for his people and Gondor.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2003)

At the final battle, the outcome is irrelevant to Théoden; it was a conscious choice of his to give himself to this greater cause that granted him his moral victory making him a true king of the highest honour. When dying after the battle he says ‘I go to my fathers; in whose mighty company I shall not now feel ashamed’[51] conveying the sense of positive pride he feels within himself as he has solved the paradox of how to be “kingly” in a world of hegemonic masculine conventions.

Théoden is contrasted by the once noble Denethor, now a leech of the crown of Gondor, sucking out its power for his own gain. Denethor goes to great lengths to ensure victory in the physical realm even willing to harness the power of the ring against his perceived enemies. Tolkien creates a level of irony surrounding Denethor- he is such an immoral king because he is a fake one, he is nothing more than a steward whose attempts at assertiveness are based on a false masculine power. Denethor claims ‘the rule of Gondor… is mine and no other man’s, unless the king should come again’[52] showing the magnitude of his corruption. This leads to Denethor creating a strong bias in the structure of his family, favouring and celebrating his first-born son Boromir’s conformity to the hegemonic model of masculinity. He shows selective pride in being a father, a man’s greatest purpose in this world, and is a negative representation of fatherhood and masculinity. By the climax of the trilogy, Denethor becomes consumed by greed and grief. The news of Boromir’s death breaks him mentally and he is now unable to cope, riddled with grief, descending into madness.

Tolkien illustrates Denethor’s twisted, deluded, and despairing disposition, when he sends Faramir out to recapture Osgiliath against unwinnable odds. Fuelled by the desire to please his father, Faramir returns from Osgiliath heavily wounded however Denethor is so deluded that he assumes Faramir is dead, arranging a funeral pyre for Faramir and himself. This is an act he sees as the ultimate act of honour giving himself a warrior’s death at his own hands.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2003)

In truth this is an act of cowardice and abandonment of his people. Where Théoden rides head on into battle with his people by his side, Denethor scurries away with no real pride or honour. Denethor’s suicide is a powerful contrast to Théoden who gives his own life in pursuit of a world free from the evil threatening Middle-earth.

Strength and Resilience

Other masculine qualities can be seen such as embodying strength and prevailing against adversity in a positive manner. Tolkien presents Faramir’s psychological resilience from his paternal and fraternal figures. Faramir, in contrast to his revered older brother Boromir (the medieval knight) is more of a Renaissance’s figure and romantic new age man.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (Extended Edition), New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2003)

Unlike his father, Faramir recognizes that a steward only holds the power in the absence of the true leader- Aragorn. Faramir accepts the situation with humility in the place of violence contrasting when we see in the afore mentioned modern films. He simply accepts Aragorn in the position of power and asks ‘My lord, you called me. I come. What does the king command?’ showing the humbleness his brother lacked. The relationships of the brothers may have been influenced by Tolkien biological brother or his platonic brothers of the T.C.B.S and those made in the war. Significantly he is also a man interested in literature, art and a world which does not hold war at its centre.

Much alike the other traits there is also an element of duality to the resilience in The Lord of the Rings. In a tale of battles and war,Frodo and Sam also show physical strength delivering the ring to Mount Doom- the primary task of this great fable. These smaller more quotidian traits carry a didactic weight suggesting by their example that everyone can carry a sense of resilience akin to characters of The Lord of the Rings in 21st century life. Tolkien simultaneously critiques and celebrates hegemonic masculinity, not shaming but warning readers of the fate of those who take it to extreme lengths and enter the world of ‘hypermasculinity’[53]. Masculinity is ultimately shown in a positive light not in an excessive brutish manner but simply and beautifully, particularly if coupled with traits more commonly considered feminine.

Feminine Hegemonic Traits in Middle-Earth

Whilst hegemonic masculinity understandably dominates The Lord of the Rings due the lack of feminine characters, I believe there is still a feminine aura at the heart of the story. The traits society ascribes to women such as emotional openness, dependency and gentle ness can be seen within the male characters alongside and enhancing their masculinity.

The gift of Emotional Availability

Aragorn’s refusal of the ring, letting Frodo continue his journey illustrates his emotion awareness and ability to look outside himself. To Aragorn, the ring is a symbol of his father’s mistake and at this pivotal moment he recognises the chance to follow a different path through honesty and selfless. When physically refusing the ring, he brings himself down to Frodo’s height, showing he does not think himself above anyone. Instead of looming above Frodo, the small hobbit, this gesture symbolises his sense of equality and respect, a gesture echoed when he kneels again as king before Frodo and his friends at his coronation.

The Lord of the Ring: The Fellowship of the Ring, New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2001)

He confesses to Frodo with tears in his eyes, ‘I would have gone with you until the end, into the very fires of Mordor’[54], laying his emotions bare for Frodo to see him as he is and not play into the toxic male trope. Aragorn rejects the hegemonic masculine idea of being stoic and simply enduring, rejecting the opportunity to seize power for himself. Instead, he allows himself to embrace hegemonic femininity for a moment to give Frodo the confidence he needs to complete his task and save Middle-Earth.

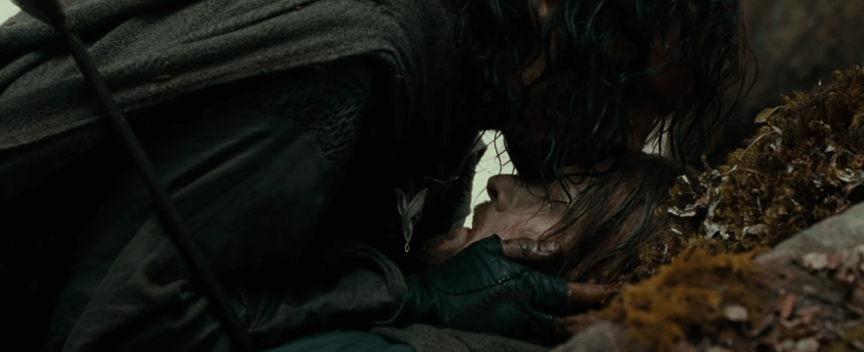

Boromir’s death is another key moment of emotional availably, albeit brief, allowing for Boromir to gain redemption and forgiveness in death. The rivalry Tolkien presents between the two characters challenges the stereotypical masculine competitiveness and instead creates more of a feminine interaction and dynamic. They careful reveal their mirrored doubts, worries, and fears for the future. They realise their share the motivation of nationalism and Aragorn reassures a dying Boromir he ‘will not let the White City fall. Nor our people fail’[55] in Boromir’s honour. Only when facing death Boromir accepts his mistakes and acknowledges the power the ring had over his mind. Boromir confesses to Aragorn ‘I would have followed you, my brother. My captain. My king’[56] these terms of endearment and affection illustrate a powerful friendship of two young men embracing each other for who they are including their flaws.

The Lord of the Ring: The Fellowship of the Ring, New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2001)

The simple act of a kiss to forehead and staying with the dying Boromir creates a moment of raw emotion and tender vulnerability, challenging the patriarchal expectations of manliness and fraternising.

Dependency on others

The hegemonic idea of men being independent and women being dependant is challenged by Tolkien through the structure of the Fellowship. Although starting with nine individuals, and although there are deaths and the group split up through the journey ultimately it is their sense of true comradery that brings them back to each other.

The Lord of the Ring: The Fellowship of the Ring, New Line Cinema by Peter Jackson (2001)

Tolkien recreates a group dynamic akin to the T.C.B.C and Lancashire Fusiliers in the fellowship that at their core relies on trust and love beyond self. No one member of the fellowship could have saved Middle-Earth, rather it is together they succeeded; they needed Frodo’s bravery, Sam’s determination, Gandalf’s wisdom, Aragorn’s sword, Legolas’s bow, Gimli’s axe and Boromir’s sacrifice.

Conclusion: the didactic message of Lord of Rings and its potential to be an antidote to toxic masculinity?

The Lord of the Rings ultimately and significantly embodies both hegemonic masculinity and femininity in a simultaneously traditional and non-traditional manner. Tolkien creates a beautiful expression of manhood that, like a sword, is strongest when double edged with femininity and masculinity. Many cultures embrace this concept, the most prominent is in North American where among the indigenous people there are some called “two spirits”[57]. They believe everything that exists has come from the Spirit World and that having the spirit of a man and the spirit of a woman a person is more spiritually gifted than the typically masculine male or feminine female. Perchance if the hegemonic model of gender embraced cultures such as the indigenous North Americans and used texts such as The Lord of the Rings to educate, we could solve the crisis of toxic masculinity.

Bibliography:

Allison, Amy. ‘Knight’s Code of Chivalry’, 11 April 2013.

‘Analysis of Sam as the Hero in “Lord of the Rings” (An Essay) | by Kelsi Lynelle | Medium’. Accessed 27 December 2022. https://medium.com/@kelsilynelle/analysis-of-heroism-in-lord-of-the-rings-an-essay-881fa04bd5ed.

Beard, Mary. Women and Power: A Manifesto Updated. Profile Books, 2017, 2017.

Beauchamp, Zack. ‘Incel, the Misogynist Ideology That Inspired the Deadly Toronto Attack, Explained’. News and Journalism. Vox, 25 April 2018. https://www.vox.com/world/2018/4/25/17277496/incel-toronto-attack-alek-minassian.

Bowles, Nellie. ‘Jordan Peterson, Custodian of the Patriarchy’. The New York Times, 18 May 2018, sec. Style. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/18/style/jordan-peterson-12-rules-for-life.html.

Brain, Jessica. ‘The White Feather Movement’. Historic UK (blog), 8 January 2022. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/White-Feather-Movement/.

Chevat, Zev. ‘Boromir’s Tender Death Scene Highlights LotR’s Soft Masculinity’. Polygon (blog), 23 June 2021. https://www.polygon.com/lord-of-the-rings/22547637/boromir-death-scene-lord-of-the-rings-masculinity.

Tolkien Gateway. ‘Christopher Wiseman’, 30 October 2022. https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Christopher_Wiseman.

C.Psych, Jacques Legault. ‘Jordan Peterson, Masculinity and the Alt-Right.’ Medium (blog), 23 February 2019. https://medium.com/@jacquesrlegault/jordan-petersons-paradox-and-the-alt-right-861e3482842b.

Das, Shanti. ‘Inside the Violent, Misogynistic World of TikTok’s New Star, Andrew Tate’. News and Journalism. The Guardian, 6 August 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/aug/06/andrew-tate-violent-misogynistic-world-of-tiktok-new-star.

Domínguez Ruiz, Beatriz. ‘J.R.R. TOLKIEN’S CONSTRUCTION OF MULTIPLE MASCULINITIES IN THE LORD OF THE RINGS’. ODISEA. Revista de Estudios Ingleses, no. 16 (21 March 2017). https://doi.org/10.25115/odisea.v0i16.295.

Doughan MBE, David. ‘J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch’. The Tolkien Society, 19 May 2021. https://www.tolkiensociety.org/author/biography/.

Finn, Amy. ‘180 Jordan Peterson Quotes on Life, Love, and More’, 17 May 2021. https://www.quoteambition.com/jordan-peterson-quotes/.

Genter, Elizabeth Nicole. ‘The Association Of Masculinity Themes In Social Network Images And Sexual Risk Behavior’, n.d., 27.

‘Gondor | The One Wiki to Rule Them All | Fandom’. Accessed 14 November 2022. https://lotr.fandom.com/wiki/Gondor.

Hardy, Sam. ‘Andrew Tate Quotes: 50+ Most Outrageous And Controversial’. Andrew Tate Quotes: 50+ Most Outrageous And Controversial, 12 August 2022. https://www.downtimebros.com/andrew-tate-quotes-50-most-outrageous-and-controversial/.

‘How Long Did It Take to Film The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit Trilogies?’ Accessed 11 November 2022. https://fictionhorizon.com/how-long-did-it-take-to-film-the-lord-of-the-rings-and-the-hobbit-trilogies/.

John Wick. Action/ Crime/ Thriller, 2015.

Levsen, Sonja. ‘Masculinities’, 7 January 2015, 4.

McKee, Tori. ‘Opinion: What Ancient Greece Can Teach Us about Toxic Masculinity Today’. Blog. University of Cambridge: News (blog), 8 February 2018. https://www.cam.ac.uk/news/opinion-what-ancient-greece-can-teach-us-about-toxic-masculinity-today.

Tolkien Gateway. ‘Rohan’, 28 October 2022. https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Rohan.

Romano, Aja. ‘How the Alt-Right’s Sexism Lures Men into White Supremacy’. News and Journalism. Vox, 26 April 2012. https://www.vox.com/culture/2016/12/14/13576192/alt-right-sexism-recruitment.

Rubarth, Scott. ‘Competing Constructions of Masculinity in Ancient Greece’. Athens Institute for Education and Research 1, no. 1 (January 2014): 12.

Taken. Action/Crime/Thriller, 2008.

Tolkien Gateway. ‘T.C.B.S.’, 9 September 2014. https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/T.C.B.S.

Tolkien Gateway. ‘The Battle of the Eastern Field’, 12 January 2020. https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/The_Battle_of_the_Eastern_Field.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Fantasy/ Adventure. Alliance films, 2001.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Fantasy/ Adventure. Alliance films, 2003. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0167260/.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Fantasy/ Adventure. Alliance films, 2002.

The Song of Roland. Penguin Publishing Group, 1990.

‘The “two-Spirit” People of Indigenous North Americans | Antony and the Johnsons | The Guardian’. Accessed 29 December 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/oct/11/two-spirit-people-north-america.

‘Theorist Judith Butler Explains How Behavior Creates Gender: A Short Introduction to “Gender Performativity” | Open Culture’. Accessed 14 November 2022. https://www.openculture.com/2018/02/judith-butler-on-gender-performativity.html.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Fellowship of the Ring. HarperCollins Publishers, n.d.

———. The Hobbit. HarperCollins Publishers, 2009.

[1] David Doughan MBE, ‘J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch’, The Tolkien Society, 19 May 2021, https://www.tolkiensociety.org/author/biography/.

[2] ‘The Battle of the Eastern Field’, Tolkien Gateway, 12 January 2020, https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/The_Battle_of_the_Eastern_Field.

[3] ‘T.C.B.S.’, Tolkien Gateway, 9 September 2014, https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/T.C.B.S.

[4] ‘Christopher Wiseman’, Tolkien Gateway, 30 October 2022, https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Christopher_Wiseman.

[5] J.R.R Tolkien, The Hobbit (HarperCollins Publishers, 2009).

[6] ‘How Long Did It Take to Film The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit Trilogies?’, accessed 11 November 2022, https://fictionhorizon.com/how-long-did-it-take-to-film-the-lord-of-the-rings-and-the-hobbit-trilogies/.

[7] Scott Rubarth, ‘Competing Constructions of Masculinity in Ancient Greece’, Athens Institute for Education and Research 1, no. 1 (January 2014): 12.

[8] Mary Beard, Women and Power: A Manifesto Updated (Profile Books, 2017, 2017).

[9] Tori McKee, ‘Opinion: What Ancient Greece Can Teach Us about Toxic Masculinity Today’, Blog, University of Cambridge: News (blog), 8 February 2018, https://www.cam.ac.uk/news/opinion-what-ancient-greece-can-teach-us-about-toxic-masculinity-today.

[10] Amy Allison, ‘Knight’s Code of Chivalry’, 11 April 2013.

[11] Allison.

[12] The Song of Roland (Penguin Publishing Group, 1990).

[13] https://files.oakland.edu/users/clason/web/grm381/capel.html

[14] https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/l/le-morte-darthur/summary-and-analysis/book-8-the-death-of-king-arthur-the-death-of-sir-launcelot-and-queen-guinevere

[15] Doughan MBE, ‘J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch’.

[16] Sonja Levsen, ‘Masculinities’, 7 January 2015, 4.

[17] Doughan MBE, ‘J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch’.

[18] Jessica Brain, ‘The White Feather Movement’, Historic UK (blog), 8 January 2022, https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/White-Feather-Movement/.

[19] Brain.

[20] Brain.

[21] Aja Romano, ‘How the Alt-Right’s Sexism Lures Men into White Supremacy’, News and Journalism, Vox, 26 April 2012, https://www.vox.com/culture/2016/12/14/13576192/alt-right-sexism-recruitment.

[22] Romano.

[23] Zack Beauchamp, ‘Incel, the Misogynist Ideology That Inspired the Deadly Toronto Attack, Explained’, News and Journalism, Vox, 25 April 2018, https://www.vox.com/world/2018/4/25/17277496/incel-toronto-attack-alek-minassian.

[24] https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/1173808-elliot-rodger-manifesto

[25] https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/1173808-elliot-rodger-manifesto

[26] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-56269095

[27] Taken, Action/Crime/Thriller, 2008.

[28] John Wick, Action/ Crime/ Thriller, 2015.

[29] Shanti Das, ‘Inside the Violent, Misogynistic World of TikTok’s New Star, Andrew Tate’, News and Journalism, The Guardian, 6 August 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/aug/06/andrew-tate-violent-misogynistic-world-of-tiktok-new-star.

[30] Das.

[31] Sam Hardy, ‘Andrew Tate Quotes: 50+ Most Outrageous And Controversial’, Andrew Tate Quotes: 50+ Most Outrageous And Controversial, 12 August 2022, https://www.downtimebros.com/andrew-tate-quotes-50-most-outrageous-and-controversial/.

[32] Nellie Bowles, ‘Jordan Peterson, Custodian of the Patriarchy’, The New York Times, 18 May 2018, sec. Style, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/18/style/jordan-peterson-12-rules-for-life.html.

[33] Jacques Legault C.Psych, ‘Jordan Peterson, Masculinity and the Alt-Right.’, Medium (blog), 23 February 2019, https://medium.com/@jacquesrlegault/jordan-petersons-paradox-and-the-alt-right-861e3482842b.

[34] Amy Finn, ‘180 Jordan Peterson Quotes on Life, Love, and More’, 17 May 2021, https://www.quoteambition.com/jordan-peterson-quotes/.

[35] Elizabeth Nicole Genter, ‘The Association Of Masculinity Themes In Social Network Images And Sexual Risk Behavior’, n.d., 27.

[36] ‘Gondor | The One Wiki to Rule Them All | Fandom’, accessed 14 November 2022, https://lotr.fandom.com/wiki/Gondor.

[37] ‘Rohan’, Tolkien Gateway, 28 October 2022, https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Rohan.

[38] Beatriz Domínguez Ruiz, ‘J.R.R. TOLKIEN’S CONSTRUCTION OF MULTIPLE MASCULINITIES IN THE LORD OF THE RINGS’, ODISEA. Revista de Estudios Ingleses, no. 16 (21 March 2017), https://doi.org/10.25115/odisea.v0i16.295.

[39] ‘Theorist Judith Butler Explains How Behaviour Creates Gender: A Short Introduction to “Gender Performativity” | Open Culture’, accessed 14 November 2022, https://www.openculture.com/2018/02/judith-butler-on-gender-performativity.html.

[40] The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Fantasy/ Adventure (Alliance films, 2003), https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0167260/.

[41] ‘Analysis of Sam as the Hero in “Lord of the Rings” (An Essay) | by Kelsi Lynelle | Medium’, accessed 27 December 2022, https://medium.com/@kelsilynelle/analysis-of-heroism-in-lord-of-the-rings-an-essay-881fa04bd5ed.

[42] Lynelle

[43] ‘Analysis of Sam as the Hero in “Lord of the Rings” (An Essay) | by Kelsi Lynelle | Medium’.

[44] ‘Analysis of Sam as the Hero in “Lord of the Rings” (An Essay) | by Kelsi Lynelle | Medium’.

[45] Zev Chevat, ‘Boromir’s Tender Death Scene Highlights LotR’s Soft Masculinity’, Polygon (blog), 23 June 2021, https://www.polygon.com/lord-of-the-rings/22547637/boromir-death-scene-lord-of-the-rings-masculinity.

[46] J.R.R Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring (HarperCollins Publishers, 1991) Chapter 10.

[47] Domínguez Ruiz, ‘J.R.R. TOLKIEN’S CONSTRUCTION OF MULTIPLE MASCULINITIES IN THE LORD OF THE RINGS’.

[48] The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, Fantasy/ Adventure (Alliance films, 2002).

[49] The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

[50] The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

[51] The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

[52] The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

[53] Domínguez Ruiz, ‘J.R.R. TOLKIEN’S CONSTRUCTION OF MULTIPLE MASCULINITIES IN THE LORD OF THE RINGS’.

[54] The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, Fantasy/ Adventure (Alliance films, 2001).

[55] The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

[56] The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

[57] ‘The “two-Spirit” People of Indigenous North Americans | Antony and the Johnsons | The Guardian’, accessed 29 December 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/oct/11/two-spirit-people-north-america.

Leave a comment