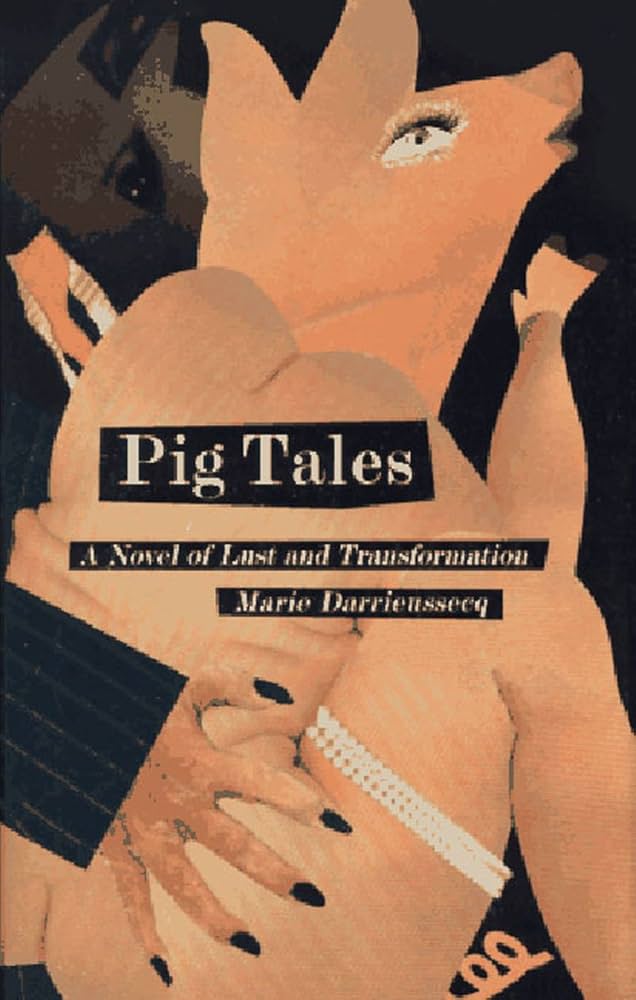

In Pig Tales (Truismes),[1] Marie Darrieussecq crafts a deeply provocative and unsettling allegory challenging the hegemonic narratives constructing gender, sexuality, and the boundaries of the human. The novel traces an unknown, unnamed woman through her surreal transformation into a ‘sow’, a female pig. [2] Her metamorphosis starkly reveals the mechanisms of patriarchal culture that reduce women to objects of consumption and control. Lying demurely at the intersection of speculative fiction and political allegory, Pig Tales becomes a rich site for interdisciplinary analysis, particularly through the combined lenses of feminist and animal theories. For at the centre of both ‘anthropocentrism’[3] and the ‘phallogocentric’[4] patriarchy lies a man. These metaphorical ideas of “human vs animal”, “man vs woman” are shaped through the powerful and provocative combination of sexuality, appearance and capitalism, and the warping of time evoking a sense of uprootedness mirroring the disorientating metamorphosis. Darrieussecq’s understanding, and representation of these symbolic oppositional ideas are informed by the pervasive pressure of the patriarchy and speciesism on the geographical and social world. As 21st Century readers or viewers, Pig Tales can be consumed critically based on intersectional feminist deconstructivism and anthrozoology. Darrieussecq produces a moving and disturbingly all-to-familiar insight into the impacts of the trials and tribulations of existing in the patriarchal human world as a female.

The protagonist’s social value under the system of the patriarchy is interconnected to her compliance to the different facets of gender norms. Feminist thinking roots itself in the dissemination and understanding of the social workings of the ‘conceptual oppositions of man vs woman’.[5] Throughout the novel we see the ‘dominance of the man and the subordination of the woman’[6] and the characters’ active engagement in these hegemonic roles. To begin, the protagonist’s value is placed on her visual conformity, spatially embodied in the narrative by the ‘perfumes and cosmetics chain’ profiting from this enforced conformity.[7] Sandra Bartky, states that ‘a woman’s body must be confined and shaped into a ‘more feminine’ form’ to meet these ideals, thus ‘the disciplinary practices of femininity produce a body on which an inferior status has been inscribed’.[8] The ‘tight fitting’ ‘employee uniforms’, looking ‘lovely and well-groomed at all times’ set a list of binary rules based on superficiality.[9] The motivations of getting the job are to solely help her further align herself to these ideals: ‘how good [she] was going to smell, about the glowing complexion’ in a futile plight of achieving male validation initially from her boyfriend and subsequently the boss and clients.[10]

This visual objectification is in a symbiotic relationship with her sexual availability, another layer of the patriarchal means of conformism. With the ‘right breast in one hand, the job contract in the other’ the boss’s sexual violation catalyses an unconscious set of behavioural patterns, the protagonist knows to ‘get down on [her] knees’ and go to ‘work’.[11] This conditioning of sexual compliance and internalisation of pride in the abuse as some form of highest compliment is active throughout the novel, illustrating how patriarchal logic infiltrates the female psyche. Moreover, her acts of disengagement with the sexual acts of the clients, ‘I didn’t want to service him anymore’, is met with instantaneous disposal, ‘dumped on the outskirts of the city’ and ‘losing a good customer’.[12] This begins the unwinnable paradox of the patriarchy regarding female sexuality. When engaged sexually she is ‘too forward, too coarse’, a ‘bitch in heat’.[13] Thus, beginning the verbal compliance, ‘I kept quiet of course and I submitted’.[14] Darrieussecq highlights how these attempts of compliance are futile as when the female body deviates from the capitalist patriarchal human desirability’s, age, whether you are a ‘frigid old hag’[15] or ‘dainty as a girl’[16], weight, or a pig-metamorphosis, any semblance of femineity is unrecognisable and monstrous. Susan Bordo affirms, ‘the rules for femininity have come to be the rules of a woman’s bodily existence’.[17] This conditioning is so internalised in the protagonist as she gains weight, she ‘began to disgust [her]self’, within her own subjectivity the patriarchy infringes.

In the protagonist’s ever-changing, pig-like state, her social and sexual value diminishes, even as the bestial impulses of her male counterparts intensify. This shift illustrates how animality and brutality are projected onto the female body through sexual violence—violence that is intrinsically connected to what Kelly Oliver terms the ‘implicit violence of our relationship with animals’.[18] Throughout the novel, animals are ‘figured negatively’, metaphorically positioned as the ‘other’ to the rational, human male.[19] Darrieussecq’s use of anthropomorphic imagery constructs a binary subjugating the female-animal, while the male-human assumes dominance through acts of violence and control. Akira Mizuta Lippit notes that animals in Western thought ‘occupy a state of disappearance,’ existing in a ‘perpetual state of vanishing.’[20] This speaks to the power dynamics of visibility: to be an animal or woman in a phallocentric society is to be present, but ultimately unseen. The protagonist reflects on this erasure: ‘they didn’t look at me to see how I was… they were preoccupied with themselves. It made them feel good to be able to feel me up.’[21] Here, she is reduced to tactile stimulus, not a subject with interiority. As Bennett and Royle argue, ‘wherever there is writing, sex and gender become equivocal, questionable and open to transformation.’[22] Darrieussecq literalises this transformation as both women and men devolve: the former into animalised objects subject to sexualisation and consumption, the latter into feral ‘savage’ aggressors with ‘wild eyes’.[23] Kelly Oliver contends that ‘the treatment of women as animals allows men to treat them with a kind of feral violence, without consequence.’[24] This is vividly embodied in Pig Tales through the semantic field of graphic sexual violence: ‘shoved something up my rear end,’[25] ‘slapped me,’[26] ‘hitting me,’[27] ‘covered with bruises,’[28] and ‘always down on all fours.’[29] The language dehumanises the protagonist, positioning her in an entirely submissive, animalistic posture. This violent domination reflects a broader patriarchal logic where bodies that fail to meet human- male- standards are rendered “un-human” and treated as expendable. The young girl from Eager’s “party” exemplifies this perfectly; while being the youthful ‘little girl’[30] idolized by the patriarchy this disposability is definite, ‘I saw him amuse himself with her for a bit and then put a bullet in her head’[31]Simone de Beauvoir reinforces this alignment when she states that ‘woman [is] always on the side of the other, of the animal, the body, the flesh’ in her groundbreaking feminist novel The Second Sex.[32] Within Darrieussecq’s narrative, femininity is placed outside of humanity and male reason. aligned instead with flesh, instinct, and abjection. To be placed ‘down on all fours’[33] is not only a literal position, but a metaphor for being located beneath the human subject in a phallogocentric order—an order that deems some bodies punishable without recognition or consequence.

As the protagonist loses her human form, she is cast into social exile—an allegory of abjection that echoes the figure of the Mad Woman in The Attic. In their landmark feminist text The Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar [34] explore how patriarchal literature confines women to the margins, casting them as either ‘angels or monsters’, ‘virgin or a Madonna Whore’.[35] The “attic” refers both literally to the upper floor of Thornfield Hall that “contains” Bertha Mason[36] and metaphorically to the symbolic space of female isolation and otherness. In Pig Tales, the protagonist is similarly ‘repressed, confined and driven crazy by forces of the patriarchy.’[37] Darrieussecq stages the maddening claustrophobia of patriarchal spaces—whether it be the perfume shop, Honoré’s apartment, or the hall of Edgar’s “New Year’s orgy”—each environment functions as a site of sexual antagonism and objectification. The protagonist’s descent into madness— ‘I was slowly losing it’—[38] evokes Gilbert and Gubar’s assertion that female characters are often driven to insanity by a system that denies them autonomy.[39] The madwoman occupies ‘an unforgiving and overlooked corner’ of the narrative and society—a position of exile, cut off from patriarchal control at the cost of utter social isolation.[40] Once she becomes monstrous, the protagonist is no longer recognisably feminine: she is laughed at, ‘snickered’ at,[41] and ultimately retreats to the ‘sewers’[42] for refuge. This dynamic is echoed in Cixous’s The Laugh of the Medusa (1975),[43] where she writes, ‘they riveted us between two horrifying myths: between the Medusa and the abyss.’[44] Like Bertha Mason, Frankenstein’s creature, and Medusa herself, Darrieussecq’s pig-woman becomes a site of horror, ridicule, and symbolic punishment for failing to conform to hegemonic femininity. These constructions of monstrosity and madness ultimately force us, as Rosi Braidotti argues, to ‘rethink the very idea of what counts as the human’—and who has the power to define it.[45]

In conclusion, Marie Darrieussecq’s Pig Tales offers a visceral and provocative critique of the systems that discipline, devalue, and ultimately dehumanise the female body. Through the protagonist’s metamorphosis into a pig, Darrieussecq lays bare the violence inherent in the patriarchal regulation of gender and sexuality, exposing how femininity is not only socially constructed but also brutally enforced. Drawing on the frameworks of Gender Studies and Animal Studies, this reading has illustrated how the protagonist is rendered abject reduced to animality, subjected to sexual violence, and exiled from human recognition. The critical theories by Bartky, Bordo, Cixous, and Oliver reveal how visual conformity, sexual compliance, and bodily discipline are central to the maintenance of patriarchal and anthropocentric power. Ultimately, the novel disrupts conventional distinctions between human and animal, subject and object, sanity and madness—forcing us to confront the unsettling truth that women, like animals, are often positioned as the silent, suffering other within dominant systems. By merging feminist and animal theory, Pig Tales becomes not just a story of transformation, but a radical allegory of resistance identifying the political and personal stakes of losing our personhood. Darrieussecq urges us to question the very foundations of what it means to be human, female, and seen.

If men act like pigs, what can I do but turn into a sow and live in a sewer.

Bibliography:

Bennett, Andrew and Royle,An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (Sixth Edition), Chapter 21: Animals and Chapter 26: Sexual Difference, 2023, Routledge.

Brontë, Charlotte (1975. Jane Eyre. Oxford World’s Classics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Darrieussecq, Marie, Pig Tales: A Novel of Lust and Transformation, 1996, Faber and Faber.

Online:

file:///Users/macbook/Downloads/ijass-2015-5(7)-382-393.pdf

[1] Darrieussecq, Marie, Pig Tales: A Novel of Lust and Transformation, 1996, Faber and Faber.

[2] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 62

[3] Bennett, Andrew and Royle,An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (Sixth Edition), Chapter 21: Animals, 2023, Routledge, 217.

[4] Bennett, Andrew and Royle,An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (Sixth Edition), Chapter 26: Sexual Difference, 2023, Routledge, 271.

[5] Bennett and Royle: Chapter 26: Sexual Difference, 268

[6] Bennett and Royle: Chapter 26: Sexual Difference, 269

[7] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 2

[8] https://faculty.uml.edu/kluis/42.101/Bartky_FoucaultFeminityandtheModernization.pdf

[9] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 3

[10] Ibid.

[11] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 2

[12] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 11

[13] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 29

[14] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 16

[15] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 11

[16] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 16

[17] https://revoltingbodies.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/the-body-and-the-reproduction-of-femininity-susan-bordo.pdf

[18] Bennett and Royle, Chapter 21: Animals, 220

[19] Ibid.

[20] Bennett and Royle, Chapter 21: Animals, 223

[21] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 15

[22] Bennett and Royle: Chapter 26: Sexual Difference, 276

[23] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 28

[24] https://feralfeminisms.com/a-conversation-on-the-feral/

[25] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 26

[26] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 28

[27] Ibid

[28] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 33

[29] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 38

[30] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 26

[31] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 95

[32] https://newuniversityinexileconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Simone-de-Beauvoir-The-Second-Sex-Jonathan-Cape-1956.pdf

[33] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 38

[34] https://ia803202.us.archive.org/32/items/TheMadwomanInTheAttic/The%20Madwoman%20in%20the%20Attic.pdf

[35] Ibid

[36] Bronte, Charlotte, Jane Eyre, 1975Oxford World’s Classics

[37] Bennett and Royle: Chapter 26: Sexual Difference, 269

[38] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 19

[39] file:///Users/macbook/Downloads/ijass-2015-5(7)-382-393.pdf

[40] https://www.vox.com/culture/22642854/still-mad-sandra-m-gilbert-susan-gubar-interview-madwoman-in-the-attic

[41] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 86

[42] Darrieussecq, Pig Tales. 73

[43] https://fleurmach.com/2013/09/06/helene-cixous-laugh-of-the-medusa-1976/

[44] Ibid

[45] https://rosibraidotti.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Braidotti-Rosi-Writing-as-a-Nomadic-Subject.pdf

Leave a comment